| By Jack E. Watson

I returned from Viet Nam in 1970 a seasoned combat pilot and a lot wiser for the experience. My first stateside assignment had me flying General Officers around in a VIP flight detachment. Quite a change from being shot at on a daily basis.

Shortly after arriving in the detachment, I was sent out as part of an aircraft accident investigation team to determine the cause of a military crash in the mountains just south of Lake Tahoe. Because of the extensive tree coverage near the crash, it took a while to find the crash site. Once the air search had located the downed aircraft, we had to helicopter into a clearing about a mile away from the crash and hike in for the investigation. Like all pilots, I hate the sight of a crashed aircraft, let alone one that has claimed a life. I'd seen people die in combat and that in itself is a numbing experience. But, to see people die by their own hand, well, that's something else. Shortly after arriving in the detachment, I was sent out as part of an aircraft accident investigation team to determine the cause of a military crash in the mountains just south of Lake Tahoe. Because of the extensive tree coverage near the crash, it took a while to find the crash site. Once the air search had located the downed aircraft, we had to helicopter into a clearing about a mile away from the crash and hike in for the investigation. Like all pilots, I hate the sight of a crashed aircraft, let alone one that has claimed a life. I'd seen people die in combat and that in itself is a numbing experience. But, to see people die by their own hand, well, that's something else.

We determined that the cause of the crash was controlled flight into terrain on a moonless night without visual cues of the rising terrain ahead of the aircraft. The pilot was a highly experienced senior aviator with several thousand hours of flight time. That accident took place well over thirty years ago. Unfortunately since then, many an aviator has ploughed unknowingly into this good green earth.

I have thought about that crash investigation many times over the years, and even though most of my flying is now in the left seat of a Boeing 757, I still race around the countryside in my Glasair Super IIRG. More than once I've had that uneasy feeling during one of my night flights or restricted visibility low-level jaunts. Remembering the past helps to put the immediate future of such flights in a different perspective.

Wandering around the display buildings at Oshkosh during Air Venture 2004, I happened to notice a couple of guys tucked into the corner of a larger vendor's booth who were attracting a small crowd as they hawked their terrain awareness display. Listening to Peter and Jeff from Aspen Avionics talk about their new low cost Terrain Awareness Display made me ponder the aftermath of that mountainside crash site years ago, and how many lives have been lost since because of similar accidental terrain incursions.

Thirty years ago technology was not at the level needed to offer low cost solutions, however controlled flight into terrain is avoidable today. The FAA has already established the need for terrain avoidance and warning systems, and mandated turbine operators to equip certain aircraft with the system. Light aircraft were for the most part not addressed by the FAA mandate, as the cost would presumably strain the already struggling general aviation economy.

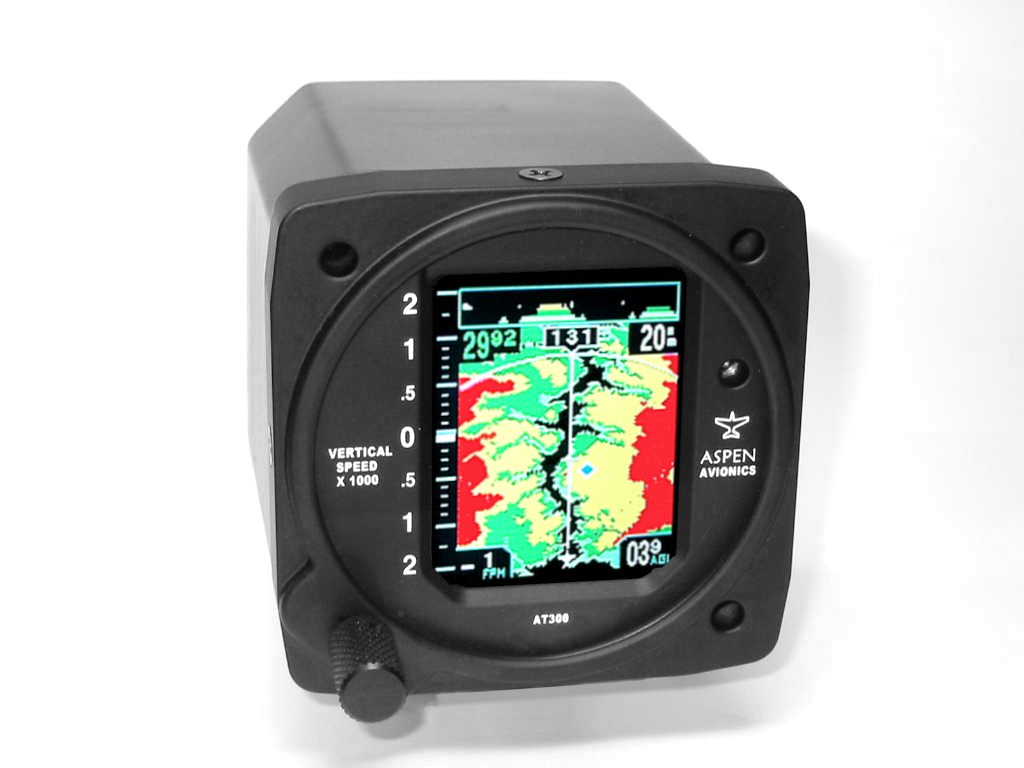

I'm proud to say that I've been proactive on dealing with this lifelong concern about obstacle avoidance, so consequently I'm one of the launch customers for Aspen Avionics AT300 Terrain Awareness Displays. The AT300 effectively provides terrain avoidance for light aircraft that the general aviation community can afford (the MSRP is $3495 for a non-certified unit, $3995 certified).

Installation is simple and also relatively inexpensive, since the AT300 is designed to replace the aircraft’s existing VSI. The unit uses the same mechanical mounting as the VSI, and only three wires are required – one each for power, ground, and GPS data. A static system leak check will be required following installation.

The AT300 display is a high-resolution sunlight readable color LCD moving map display that includes both top-view and side-view terrain presentations, a full-time vertical speed display, and remote supplemental readout of GPS navigation data. It displays surrounding terrain and obstacles in shades of red, yellow, and green. Instantaneous height above ground is also displayed whenever the aircraft is below 10,000 ft AGL.

The moving map functions of the AT300 require that the aircraft have a GPS system. The unit is compatible with virtually all panel mounted and handheld GPS navigation systems. This provides an easy upgrade to add color moving map technology to older GPS systems, since the AT300 graphically depicts the current GPS leg and active waypoint on the moving map display, and can show either side view terrain or textual GPS navigation information (current waypoint, distance, groundspeed, etc.). The unit also displays airport symbols for all hard surfaced US airports.

After receiving my AT300, the simple hookup was almost too easy. In preparation for a flight from Daytona Beach, Florida to Athens, Georgia, I managed to panel mount the instrument and wire it into my panel mounted GPS in just a few hours before the flight. (Note: At present, the instrument is for experimental aircraft only. Certification, according to Peter at Aspen, is still a few months away.)

The incredibly bright color LCD moving map display provides a wealth of information. A single rotary knob controls all functions. Each time you depress the knob the cursor moves about the screen. When it highlights a value you wish to change, just rotate the knob to the desired value (e.g. range, altimeter setting, etc.). It's dirt simple to use, even in a bouncy cockpit. To ensure accuracy, you need to update its internal altimeter setting by the rotary knob each time you set your aircraft altimeter. The incredibly bright color LCD moving map display provides a wealth of information. A single rotary knob controls all functions. Each time you depress the knob the cursor moves about the screen. When it highlights a value you wish to change, just rotate the knob to the desired value (e.g. range, altimeter setting, etc.). It's dirt simple to use, even in a bouncy cockpit. To ensure accuracy, you need to update its internal altimeter setting by the rotary knob each time you set your aircraft altimeter.

As the amber sun dipped below the western horizon of Florida, my banana yellow Glasair headed directly for Athens at 186 knots GPS ground speed. All the MOA's and restricted airspace were cold between 7FL6 (Spruce Creek Fly-In Community) and Athens. I'm not a great fan of flying single engine airplanes at night, but the addition of the Aspen instrument seemed to give me a lot more confidence about my situational awareness. I've spent many years flying airliners (34 plus), and flying high definitely has merit, especially in mountainous terrain. Flying low, although more enjoyable from a scenic standpoint, does add to the stress level at night and in marginal weather (much less mountain terrain).

The course line on the AT300 was created by my Bendix/King KLN94B GPS, showing the intended track to Athens. It was depicted as a bold magenta line across the face of the AT300 and served as a great crosscheck to the color display on the KLN94B. The instrument sits almost directly in front of me and its color is so vibrant it almost mesmerizes you. The vertical speed tape on the left side of the display provided smooth indications in its readout of my climb or descent rate and the appearance of the white bar expanding up or down on the +/- 2000 fpm scale acted as sort of a “stay on altitude” reminder.

Florida seems to grow 500-foot-plus tall radio towers everywhere just to give aviators something to hit, since it lacks any terrain of consequence. I passed several of these towers along the way, and as they marched toward me on the AT300 display as inverted "V" symbols, their whereabouts were depicted very accurately. The book says that these obstructions appear in amber when within 500 feet of your altitude, and turn from amber to red if you are within 250 feet of said obstacle. I'll take their word for it! I liked the 20-mile range the best for my 180-knot speed, and that gave me ample warning when approaching objects. Since manmade obstacles are only presented when they are within 500 feet of your altitude, the screen de-clutters itself the higher you fly above these obstructions.

Interpretation of the instruments display is all but self-explanatory. My personal rhyme for viewing the display is, "Look out for red ahead!" This applies to manmade objects as well as terrain. Simply put, if it appears in red and it's under your course line you need to take positive action to climb above, or turn away, to avoid a potential crash.

As I approached Athens, Georgia, the long shallow descent from 6,500 feet gave me newfound appreciation for what this instrument can do. It can quite frankly save your life if you keep it in your scan. It was pitch black outside, and where the darkness of night painted a jagged edge against the hilly terrain in this part of Georgia, it seemed all too easy to forget that some of those night shadows were solid rock. Only the little 3 1/8th inch instrument in front of me knew the difference.

As for the future of this unique instrument, the folks at Aspen are planning to incorporate an interface with WSI's in flight weather system (wsi.com) after the unit is OK'd for certified aircraft. I've already got the WSI box and antenna sitting on the bench in anticipation of this future upgrade. This will provide almost real time color weather depiction that can fit in just about any size airplane.

This new, affordable technology can greatly reduce the risk of general aviation pilots becoming a controlled flight into terrain statistic. For more information visit aspenavionics.com or call 505-856-5034.

Author’s Bio

Jack E. Watson is a B-757 Captain with over 34,000 hours of flying time. For fun he races airplanes. Visit his web site hawkairracing.com or contact him at hawkshow@hotmail.com with your comments or questions.

|