|

|

|

| SW Aviator Magazine is available in print free at FBOs and aviation-related businesses throughout the Southwest or by subscription. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The web's most comprehensive database of Southwest area aviation events.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Featured Site:

|

|

|

|

|

A continuosly changing collection of links to our favorite aviation related web sites.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Who Was Really First?

|

|

The Hammondsport Hoax

|

| By Larry Shields |

Wilbur and Orville Wright seated on steps of rear porch, 7 Hawthorne Street,Dayton, Ohio. Circa 1909.

Wilbur and Orville Wright seated on steps of rear porch, 7 Hawthorne Street,Dayton, Ohio. Circa 1909.

Newspaper clippings from: Scrapbooks: December 1910-March 1914, Wilbur and Orville Wright Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

|

The 100th anniversary of the first manned, heavier-than-air powered flight has passed, but all the jostling for primary credit for the Wright brothers’ feat by officials – and un-officials – throughout Ohio and North Carolina appears to be, as before, unsettled to everyone’s satisfaction. While no other state, with the possible exception of Indiana (Wilbur’s birthplace), can stake much of a claim to one of humankind’s greatest inventions, a brassy New Yorker once tried to do so.

Glenn Hammond Curtiss, from Hammondsport, NY, and co-conspirator Albert Zahm (another Ohioan) – with the urging and support of such heavyweights as the Smithsonian Institution – once tried to wrest credit from the Wrights, steal their patent, and make a great deal of money for themselves in the process.

Curtiss was a motorcycle racer who had the unfortunate habit of building airplanes that infringed on the Wright brothers’ patent. Zahm, a decorated academic, was chief research engineer for the Curtiss Airplane Company. Prior to working for Curtiss, Zahm had been on friendly terms with the Wrights. He had offered his professional services to them in 1910 regarding a patent infringement suit against Curtiss, but the Wrights turned him down.

In 1914, Curtiss, Zahm, and their attorney met to strategize ways to undermine the Wrights’ standing as pioneers, and somehow reduce the power of their patent. If they could convince a court to mitigate the invincibility of the Wrights’ patent, they stood to become wealthy producing airplanes using the Wright technology. No one had flown before the Wrights, but if Curtiss and Zahm could prove that someone had been capable of flying earlier, such evidence might serve to undercut the pioneering status of the Wrights’ patent. A “prior claim” could show that, while the Wrights were first to fly, another, Dr. Samuel Pierpont Langley (a onetime Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution), had been capable of flying before them.

|

Glenn Curtiss at the wheel of his biplane after winning the Gordon-Bennett Trophy in Rheims, France. Circa 1909

Glenn Curtiss at the wheel of his biplane after winning the Gordon-Bennett Trophy in Rheims, France. Circa 1909

|

Zahm suggested rebuilding Langley’s machine. It was called the Great Aerodrome by some, but, inasmuch as the prefix aero implies flight, this was a misnomer. Langley’s tandem-wing machine ended up in the Potomac River on each of two attempts at flight in the autumn of 1903. Langley, who died in 1906, was ridiculed in the press for his failures. His embarrassment at being bested by two Ohio bicycle makers who never graduated from high school was shared by many at the Smithsonian.

According to the book The Wright Brothers, by Fred C. Kelly, “The Smithsonian entered into a deal with Curtiss in which he was to receive a payment of $2,000, and was permitted to take the original Langley plane from the Smithsonian to his shop at Hammondsport, New York.” Curtiss wrote one of the exhibition pilots a letter saying he felt he could get his hands on Langley’s plane. “I think I can get permission to rebuild the machine, which would go a long way toward showing that the Wrights did not invent the flying machine as a whole but only a balancing device, and we would get a better (court) decision next time,” he said.

Curtiss had the Aerodrome freighted up to Hammondsport, where it was fitted with pontoons for water launches off Lake Keuka. The pontoons added weight and aerodynamic drag that worked against the machine, but many changes that Curtiss and Zahm made to the Aerodrome over two seasons of testing were beneficial, including improvements to the wing aspect ratio, camber, and angle of attack.

This technology, unknown to Langley in 1903, was derived from the Wrights’ wind-tunnel tests in November and December 1901, and was known only to them at the time. At the controls of an Aerodrome made airworthy using the Wrights’ own technology, Curtiss flew what was termed “several short hops” over Lake Keuka in 1914 and longer flights with additional modifications in 1915. The Wrights’ biographer, Fred Howard, wrote regarding a May 28, 1914 “hop” at which no unbiased observers were present, “The papers the next day were full of the news that ‘Langley’s Folly,’ mercilessly vilified for its failure in 1903, had all along been capable of flight.” Officials at the Smithsonian, which had been represented on-site by its official observer, Zahm, were elated. The Smithsonian annual report that year falsely stated that the original Langley machine flew without changes.

|

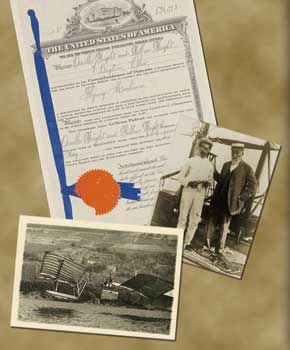

The Wright's "Flying -Machines" patent, 1906.

The Wright's "Flying -Machines" patent, 1906.

Glenn Curtiss pilots the rebuilt Aerodrome. Circa 1914

Samuel Langley with chief mechanic and pilot, Charles M. Manly. Circa 1909.

|

Orville had finally had it. “Silent truth cannot withstand error aided by continued propaganda,” he said. In counterattacking the usurpers, he employed the same deliberation and determination that had helped him and his brother conquer the skies. He counted, at a time when public prevarications could still be enumerated, 35 lies upon which Curtiss and Zahm had tried to build their case. He showed that the devices used by Curtiss on the rebuilt Aerodrome infringed on the Wrights’ original, ingenious wing-warping system of control.

Eventually the Smithsonian, too, owned up to its part in the scandal with a written confession that Orville reviewed as a condition for his donating the original Wright Brothers’ Flyer to the Smithsonian Institution.

In the end the hoax failed, and today it is barely visible in the shadow of the Wright brothers’ enormous achievement and resulting stature. Still, the whole conspiracy might have died aborning had aviation and legal cognoscenti recognized the truth hit upon by another New Yorker. On June 4, 1896, seven-and-a-half years before the Wrights flew, an unnamed editorial writer for the Binghampton (NY) Republican, predicted that bicycle makers would ultimately design and fly a heavier-than-air machine: “The flying machine will not be the same shape, or at all the style of the numerous kinds of cycles, but the study to produce light, swift machines is likely to lead to an evolution in which wings will play a conspicuous part.”

|

Click here to return to the beginning of this article.  |

|